When a Patient Declares a Penicillin Allergy

In clinical practice, few pieces of patient history carry as much downstream influence as the phrase: “I’m allergic to penicillin.” It is often documented quickly, rarely interrogated, and almost always treated as definitive. Yet this single label has implications that extend far beyond the decision to avoid one antibiotic. It influences antimicrobial spectrum, resistance patterns, adverse event risk, length of stay, and ultimately patient outcomes.

This is why understanding what a penicillin allergy label actually represents—and what it often does not—matters more than many clinicians realize.

The Prevalence Problem: Common Does Not Mean Correct

Approximately 8–10% of patients in the United States report a penicillin allergy. However, when formally evaluated, fewer than 10% of those patients demonstrate a true, immune-mediated hypersensitivity.(1,2) That means the overwhelming majority of penicillin allergy labels are either inaccurate, outdated, or misclassified.

Despite this, once the label is applied, it tends to persist indefinitely. Allergy documentation is frequently inherited across encounters without reassessment, even when the original reaction occurred decades earlier or was poorly characterized. In many cases, the reaction was a non–immune-mediated adverse effect, a childhood rash during a viral illness, or an event that would no longer meet criteria for true allergy today.

The result is a clinical environment in which a large proportion of patients are treated as if they are at high risk for severe reactions—when, in reality, they are not.

How a Penicillin Allergy Label Alters Clinical Decision-Making

When penicillins are removed from consideration, clinicians are often forced to select alternative agents that are broader in spectrum, less effective for the target pathogen, or associated with higher toxicity.

Common downstream consequences include:

- Use of broader-spectrum antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, clindamycin, or vancomycin

- Increased risk of Clostridioides difficile infection due to disruption of normal gut flora

- Higher rates of antimicrobial resistance, both at the individual and population level

- Greater likelihood of adverse drug reactions unrelated to allergy

- Increased cost of care and, in hospitalized patients, longer lengths of stay

Importantly, these outcomes are not theoretical. Multiple studies have demonstrated that patients labeled as penicillin-allergic experience worse antimicrobial-related outcomes compared with those without the label, even when the underlying infection and comorbidities are similar.(3-5)

This is why a penicillin allergy label should be viewed not as a benign precaution, but as a modifier of care with real clinical consequences.

Antibiotic Stewardship and the Cost of Inaccuracy

From an antibiotic stewardship perspective, inaccurate allergy labels represent a silent but significant barrier to optimal therapy. Beta-lactam antibiotics—including penicillins and cephalosporins—remain first-line therapy for many common infections because of their efficacy, safety profile, and relatively narrow spectrum.

When these agents are unnecessarily avoided, stewardship principles are compromised. Clinicians may feel justified in choosing “safer” alternatives, but those alternatives often carry greater long-term risk for both the patient and the healthcare system.

This is why stewardship is not only about choosing the right antibiotic, but also about ensuring that unnecessary exclusions are removed when possible.

Not All Allergies—and Not All Beta-Lactams—Are the Same

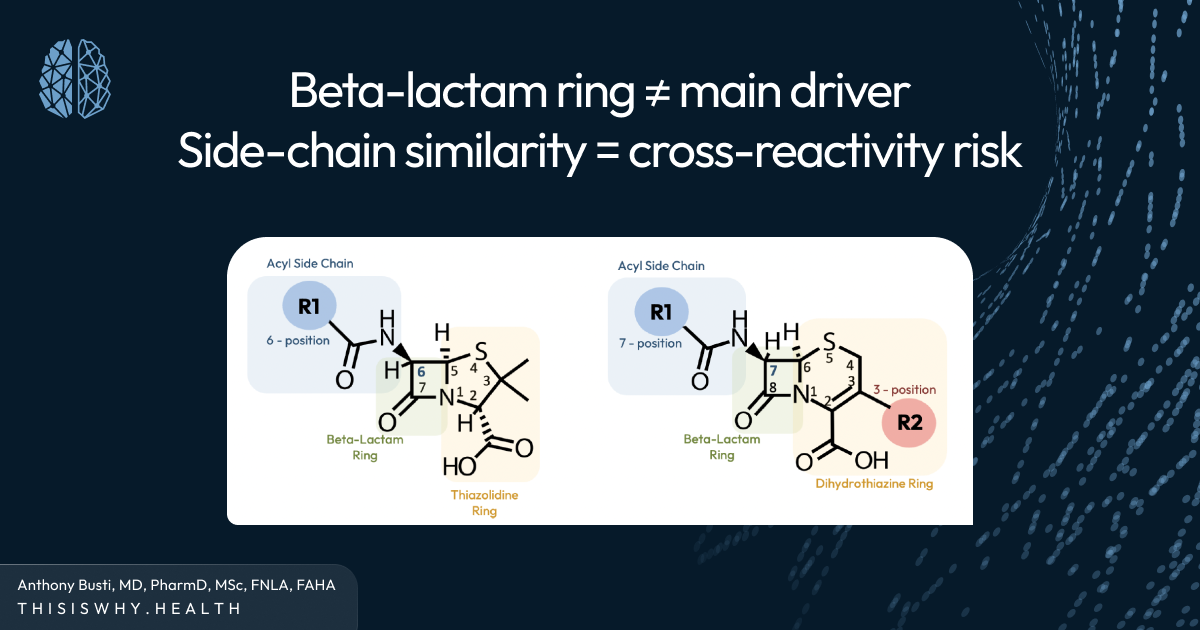

A critical error in clinical reasoning is treating all beta-lactam antibiotics as interchangeable from an allergy perspective. In reality, immune cross-reactivity is not driven by the beta-lactam ring itself, but by structural side chains that vary significantly across agents.

This distinction matters because many patients labeled as penicillin-allergic can safely receive certain cephalosporins, particularly later-generation agents that do not share similar side-chain structures. (See the video at the end of this article that explains why!)

When clinicians fail to appreciate this nuance, they may exclude an entire class of highly effective antibiotics unnecessarily. The result is a cascade of suboptimal choices driven not by evidence, but by uncertainty.

This is why understanding why cross-reactivity occurs is more valuable than memorizing which drugs are “allowed” or “forbidden.”

The Role of Allergy History: Asking Better Questions

One of the most powerful tools clinicians have is also one of the simplest: a careful allergy history.

Key questions include:

- Whatwas the reaction?

- Howlong ago did it occur?

- Wasit immediate or delayed?

- Were there features suggestive of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity (e.g., urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm, anaphylaxis)?

- Has the patient tolerated similar antibiotics since?

In many cases, this brief clarification alone can reclassify the patient’s risk and open the door to safer, more effective therapy.

For patients with unclear or low-risk histories, formal allergy testing or graded challenges may be appropriate. While this requires resources, the long-term benefits—both for the individual patient and for antimicrobial stewardship—are substantial.

Why This Matters at the Bedside

The impact of a penicillin allergy label is rarely confined to a single encounter. Once applied, it shapes care across hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and transitions between providers. Each subsequent clinician inherits the label and its assumptions.

This is why the decision to accept, question, or clarify a reported allergy is not trivial. It is an opportunity to improve care not only today, but for years to come.

When clinicians understand the why behind antibiotic allergies—rather than relying on oversimplified rules—they are better equipped to balance safety with efficacy. They can individualize therapy, reduce unnecessary risk, and preserve the utility of our most valuable antimicrobial agents.

Bringing It All Together

A penicillin allergy label is more than a checkbox in the medical record. It is a powerful determinant of clinical behavior, antimicrobial selection, and patient outcomes. Most of these labels are inaccurate or at least incomplete, yet their influence persists.

This is why moving from reflexive avoidance to evidence-based assessment matters. By understanding the mechanisms behind allergy, the true risks of cross-reactivity, and the consequences of alternative therapy, clinicians can make more informed decisions that benefit both their patients and the broader healthcare system.

For those who want a deeper, visual explanation of how antibiotic structure—not drug class alone—drives cross-reactivity risk, our companion video walks through this concept step by step and connects the science directly to bedside decision-making.

Because when you understand the why, you can master the how—and provide care that is both safer and smarter.

References

- Wada KJ, Calhoun KH. US antibiotic stewardship and penicillin allergy. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Jun;25(3):252-254. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000364. PMID: 28426527.

- Eiland LS, Lteif L. The Basics of Penicillin Allergy: What A Clinician Should Know. Pharmacy (Basel). 2019 Jul 17;7(3):94. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy7030094. PMID: 31319528.

- Blumenthal, K.G., et al. Risk of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: population based matched cohort study. BMJ 2018;361:k2400

- Macy, E., & Contreras, R. (2014). Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 133(3), 790–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

- Conway EL, et al. Impact of Penicillin Allergy on Time to First Dose of Antimicrobial Therapy and Clinical Outcomes. Clin Ther, 2017 Nov;39(11):2276-2283. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.09.012

Anthony J. Busti, MD, PharmD, MSc, FNLA, FAHA